CEO Micah Kāne and Senior VP Lauren Nahme explain funding decisions, and how efforts to rebuild Lahaina may ultimately drive down costs of simple homes.

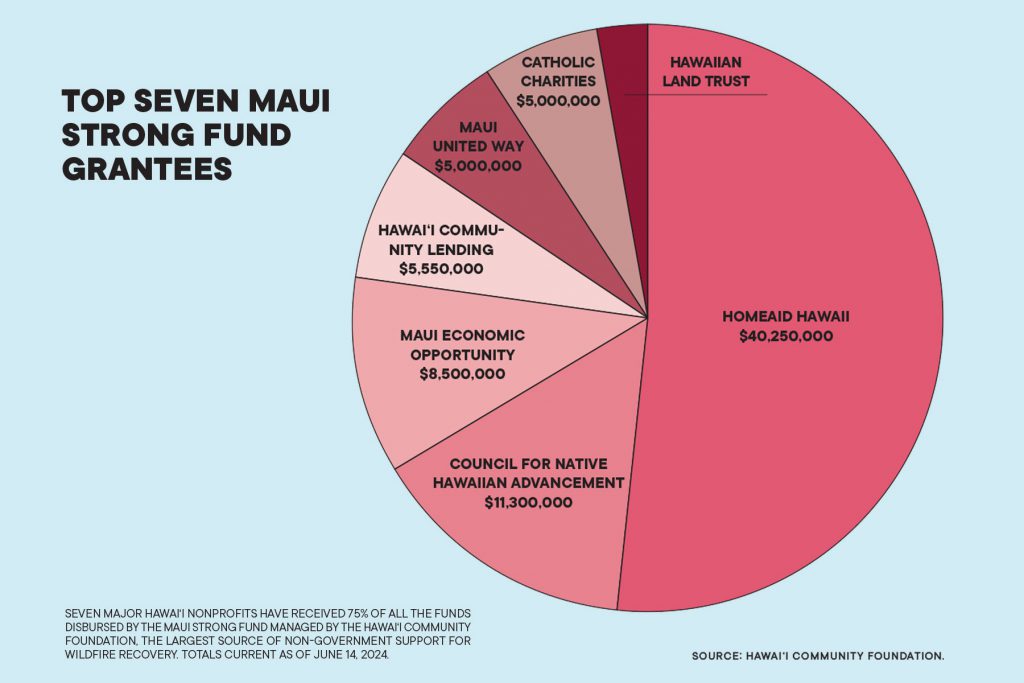

The Hawai’i Community Foundation’s Maui strong fund raised $194 million by June 28 and has already allocated $107 million for relief efforts on the Valley Isle. Of that allocated, 52% has gone to housing; $27% to health and social services; 20% to economic resilience and 1% for natural, historical and cultural projects.

HCF says that so far, 583 grant applications have been received and 234 approved. Examples of approved grants are all over the map. Some $55 million from the Maui Strong Fund has covered rental assistance, payments to host families and interim housing, including $40 million for the 450-unit Ka La‘i Ola temporary housing project that broke ground April 30.

Another $1.9 million is helping to build a Maui Fire Department station in Olowalu, south of Lahaina, plus $2 million for specialized fire trucks. Additionally, $20 million goes toward emergency response, mobile services, distribution of relief and grief counseling; $21 million for cash assistance and workforce development; and $2 million to make the watershed more resilient, remove contaminants and improve coastal water quality. You can read specifics about the grants at tinyurl.com/mauigrants.

How Decisions Are Made

HCF CEO Micah Kāne and Lauren Nahme, senior VP of Maui Recovery Effort, answered dozens of my questions in three recent interviews, including how HCF’s spending decisions are made, how the foundation is facilitating further donations for Maui and the biggest question of all: how to make future housing affordable to people on Maui and across Hawai‘i.

Kāne says HCF’s Maui relief spending follows the foundation’s overall model. “We spend a lot of resources trying to make people comfortable for today. Most of our transactional grants to food banks, homeless shelters and other providers are serving immediate needs,” he says.

“But at the same time, we’re trying to get far upstream to mitigate the challenges we face and reduce that problem pipeline substantially. The Maui experience has been that, times 200.”

Both Kāne and Nahme agree that as many as 10 years of hard work, rebuilding and pain lie ahead, but they also express optimism, both for the work already accomplished by government, relief organizations and people on Maui, and in the hope for a better future.

“As challenging as the last 10 months have been,” Kāne says, “I’m more inspired today than at any time in my career by the possibilities for the future of Maui and the role it can play to prove we can make Hawai‘i affordable – especially around housing.”

Under current conditions, affordable housing is virtually impossible to build on Maui or anywhere in Hawai‘i, so we have to change the system, Kāne says. For how he proposes we do that, read further in this story, where we dive into the costs of building even simple homes and the solution he sees. But for now, I will keep this story’s focus on the bigger picture of relief for Maui.

The needs in West Maui are enormous and matched by countless requests for funding plus tension, clamor and anger – in meetings, on social media and elsewhere – with accusations about unmet needs, ignored people and misspent money. These actions are not unique to Maui; they happen after every disaster.

“Didn’t Reinvent the Wheel”

In the aftermath of the Lahaina disaster, Nahme says, “We didn’t reinvent the wheel.

FEMA has a framework that has guided us” in allocating resources on immediate needs and long-term spending. FEMA’s framework includes eight principles:

- Individual and family empowerment

- Leadership and local primacy

- Pre-disaster recovery planning

- Engaged partnerships and inclusiveness

- Unity of effort

- Timeliness and flexibility

- Resilience and sustainability

- Psychological and emotional recovery

For HCF, the principle of “engaged partnerships” means coordinating with everyone else on the ground, including three levels of government, myriad nonprofits and community organizations, companies and other stakeholders. “The more that we align with others, the better it can be coordinated with less waste and better strategy,” Nahme says.

She gives an example. “In the week after the fire, we met with the mayor and have met with him basically every week since. That’s because every disaster starts and ends locally. Maui could not manage the disaster on their own, but they have to be in the driver position … especially over the long term.”

In October, Maui County created its Office of Recovery and set six areas that would shape the effort. Nahme says HCF’s spending tracks with those six categories:

- Community planning

- Housing, both interim and permanent

- Infrastructure

- Natural and cultural resources

- Health and social services

- Economic recovery

“Spent the Time Listening”

Many people talk about “the community” driving short-term and long-term relief decisions on Maui, but finding consensus among something as amorphous as “the community” is difficult. Maui Mayor Richard Bissen and the Maui County Council are obvious choices to consult, since the voters of Maui elected them. Beyond them, relief organizers and leaders are turning to trusted relationships and then branching out from there, Kāne and Nahme say.

Right after the fire, the first organizations HCF consulted about spending decisions on Maui were nonprofits that the foundation had worked with for a long time: Maui Economic Opportunity, Maui United Way, Catholic Charities and Maui Food Bank. “Those relationships are built up over decades and they’re trusted opinions,” Kāne says.

“Later, you go broader in where you get your intel because you’re making bigger investments with more people in the decision-making process, whether it’s the County Council, mayor, governor, a government department, another benefactor or philanthropic organization, a corporate entity that wants to make a major contribution, a landowner.”

At the same time, you’re listening to ordinary people on a very local level, Nahme says. “Just within the Lahaina community, there’s neighborhoods, there’s streets. We’ve definitely spent the time listening … and we also lean on nonprofits that are directly serving on the ground.”

She adds: “We know HCF is not going to set the overall vision and strategy. We have to be very responsive to the actual disaster and then get the community and those directly affected to be in the lead position, deciding what happens, especially over the long term.”

Kāne says HCF looks at what government and other nonprofits are already doing, and then tries to tackle the unmet needs – immediate and long-term.

How to Make Housing Affordable

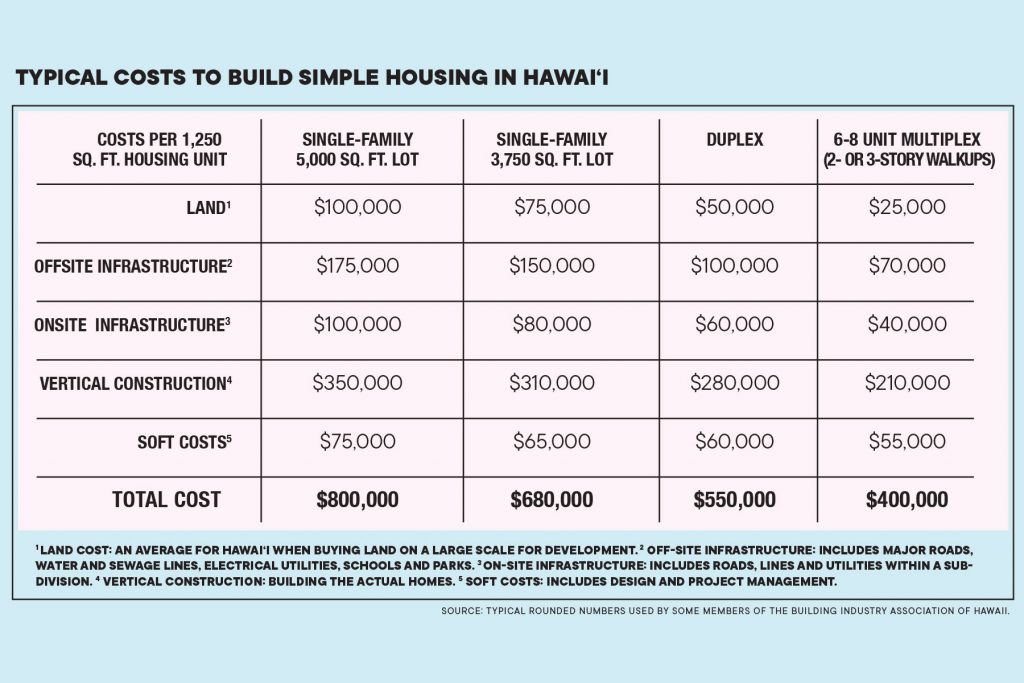

Kāne says Hawai‘i needs to disrupt the financial model of affordable home construction. First, he acknowledges that overregulation, financing and uncertainty drive up the cost of housing, but before addressing those things, he wants to focus on five main drivers of housing costs in Hawai‘i: land; off-site infrastructure; on-site infrastructure; the actual building of the home, which is often called vertical construction; and the fifth driver, the relatively modest “soft” costs such as design and project management.

In the chart below we do the math on those five costs, using numbers for building simple homes – “carport, no enclosed garage, no PV or any fancy stuff,” Kāne says – that are common back-of-the-envelope calculations used by some members of the Building Industry Association of Hawaii.

A Blueprint for Affordable Housing

None of those totals match anyone’s definition of “affordable.” For single-family homes and duplexes, your costs total hundreds of thousands of dollars before you actually build the house.

“We can talk about regulation until we’re blue in the face but we will never meet affordability unless we eliminate land costs, eliminate off-site infrastructure costs, and probably in some cases eliminate some on-site infrastructure costs, such as some of the interior roads,” Kāne says.

“You want to get a market unit at about $500,000, so families can actually start saving money (after buying a home). A small subdivision lot where it’s in the high threes, low fours. And a duplex where somebody can enter the market at about $200,000. That’s the ideal state.”

That can only happen if the land comes at no cost and government pays for the off-site infrastructure, he says. “That’s what taxpayer dollars are supposed to be for: major roads, water, sewer and public facilities. That’s not really the responsibility of the private sector. The handoff on infrastructure should happen at the housing site.”

Kāne says public leaders are having conversations within those parameters now: How to eliminate land and off-site infrastructure costs, plus reduce the costs of regulation and capital to bring down the cost of building housing on Maui and throughout Hawai‘i.

The Ka La‘i Ola temporary housing project has elements of that business model. HCF’s Maui Strong Fund contributed $40 million to the project. The 450 studios and one-, two-, and three-bedroom units are designed to be occupied for up to five years. But the project is also a long-term investment in off-site and on-site infrastructure.

Still Asking for Donations

HCF is still asking for Maui donations, almost a year after the fire, including both general donations and more targeted donations from big donors.

“We set up a funders’ collaborative with other philanthropic organizations that want to support Maui but are not tapped in. We’re collaborating with them on a process to make it easy for say, an entity with a proposal for an interim housing project or a mental health hub or whatever, that entity can go to this group and pitch one time. All the philanthropic organizations will hear it. If it’s aligned with someone’s board and mission, they can support it, and we can coordinate among the funders to have shared reporting and monitoring so that the grantee doesn’t have to do it separately for five or six funders.”

One group receiving support comprises homeowners who lost their homes in the fire and need a bridge until they can move back into their rebuilt homes. HCF coordinated a $7 million grant funded by banks, their foundations and the Federal Home Loan Banks that is going to Hawai‘i Community Lending, a nonprofit mortgage lender.

“That money is going to be used household by household for homeowners struggling to get their full insurance proceeds, because they don’t know how to support themselves or whatever reason, working with the bank or mortgage holder, figuring what the rebuild cost is, and what government programs are there to fill that gap,” Nahme says.

“The goal is to ensure that anybody who owns a home and is an owner occupant will be able to keep it and stay there.”

Nahme says the future is daunting “but there are bright spots. The remediation and clearing of lots and allowing folks to go back to their places and start rebuilding is happening at least a year earlier than the earliest projection. They’ve cleared over 1,000 lots already.”

And there is energy about building the future. “There’s always going to be tensions, but I really believe in this community. They’re going to fight through those challenges. So pre-fire issues they had, they got worse during the disaster, like housing, energy costs, education and prospects for economic development and diversification. I think that changes will happen with all of those things and people are ready to talk about it.”

See article at Hawai‘i Business Magazine