The government program helped over 13,000 households. One reason it succeeded may have been that people who had experienced housing instability had a seat at the decision-making table.

Mother of four Aura Reyes lost her O‘ahu home over 10 years ago, but she can still remember the experience like it was yesterday.

“When you first come out on the street and when you first lose your home, it’s hard, it’s traumatic,” she says. “Just the uncertainty and the not knowing and the just – mentally, emotionally – just everything.”

She, her husband and children found housing in 2018. In May 2020, Reyes was appointed to a state legislative subcommittee to address housing and homelessness during the pandemic. She wanted to help prevent tens of thousands of renter households from losing their homes like she did.

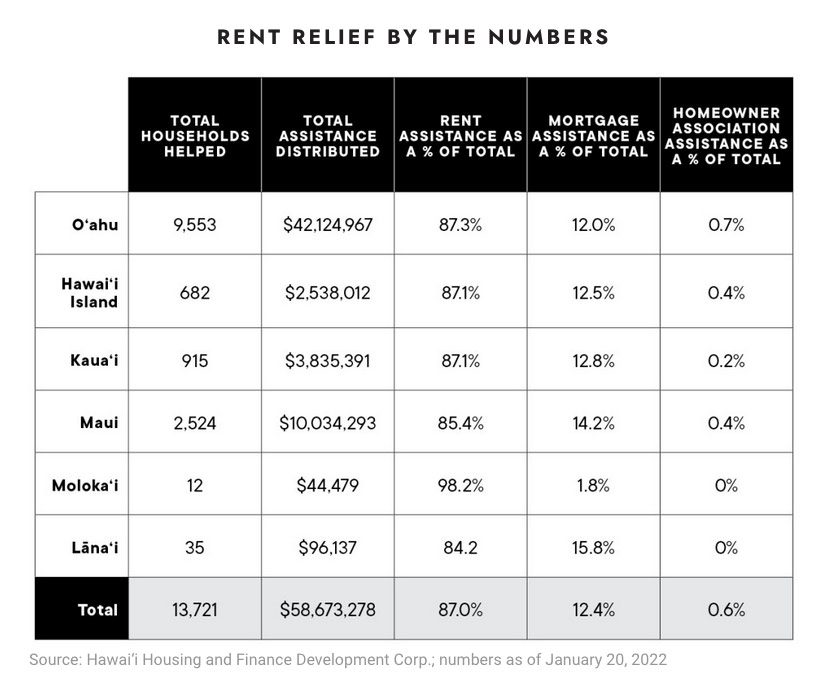

The group spent months creating a temporary state rent and mortgage relief program that ultimately distributed nearly $59 million on behalf of 13,700 households in three months. The program was considered a leader in distributing housing assistance funded by the U.S. Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act. An analysis by the Hawai‘i Budget and Policy Center found that the 2020 Hawai‘i program distributed more funds per capita than any other state effort in the country.

“I think sometimes we do undercount the disasters that didn’t happen,” says Suzanne Skjold, chief operating officer at Aloha United Way, one of two nonprofits that distributed the assistance. “But this really did prevent tens of thousands of families from becoming potentially houseless, either temporarily or permanently. And I know … that is very often the ALICE (asset limited, income constrained, employed) population families who are working, who don’t have a lot of assets to be able to fall back on if they don’t have income.

“Programs like this that can fill that gap and help people to stay stable and in housing, it’s so critical. It’s exactly what we need to be doing to make sure that 50%, 60% of our population can continue to live in Hawai‘i and be able to thrive.”

Urgent Need for Help

A dark cloud loomed over Hawai‘i as the Covid-19 pandemic dragged into May 2020: About 22% of Hawai‘i’s workforce was unemployed and the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that nearly 30% of Hawai‘i’s adults missed the previous month’s housing payment or had little confidence that their household could pay the next month’s rent or mortgage on time.

Things weren’t projected to improve as the year progressed. An analysis by UHERO, the UH Economic Research Organization, and the Hawai‘i Budget and Policy Center looked at the second half of 2020 and estimated that between 40,000 to 45,000 renter households would be unemployed, lose their increased unemployment benefits once federal pandemic unemployment compensation expired and would not be receiving other rental assistance come July 31. About 21,500 of these households would be at risk of losing their housing, including about 7,500 that would be at extreme risk.

It’s no surprise that several members of the legislative subcommittee on housing and homelessness felt a sense of urgency.

“The stuff that sticks out most to me was, I think, the hopeful feeling of the way that this shared crisis was bringing together all these different stakeholders and perspectives to really provide focus to the things that were most important at the time,” he says.

Decision-Makers

Those stakeholders included CEOs and executives of banks and philanthropic organizations, nonprofit leaders, policy experts, and officials from the Hawai‘i Housing Finance and Development Corp. and the governor’s office. Also at the decision-making table were people who had experienced housing instability and homelessness, like Reyes, who represented Ka Po‘e o Kaka‘ako, a group of current and formerly houseless individuals trying to change the way homelessness is addressed. The subcommittee fell under the state House Select Committee on Covid-19 Economic and Financial Preparedness.

Thornton says it’s rare to see community members who have experienced housing instability or homelessness involved in decision-making, but the subcommittee’s chair, James Koshiba, thought it was important to include them.

Koshiba is a co-founder of Hui Aloha, which brings together houseless people and others to work on service projects. Several years ago, Koshiba spent a week living on Kaka‘ako’s streets to better understand the impacts of homelessness policies. That experience, he says, made him realize that some of the flaws in Hawai‘i’s housing and homelessness systems exist because of a disconnect between the goals of those systems, the people making decisions and the people experiencing the systems’ impacts.

By including individuals directly affected by homelessness and housing instability, other subcommittee members better understand what it’s like to get housing assistance in normal times, how the current systems’ rules impact those in need and the hoops they must jump through to get help, Koshiba says.

Their involvement also made the crisis tangible for group members who previously may not have personally known anyone who’s experienced housing instability or homelessness.

See full article at Hawaii Business Magazine, June 13, 2022 by Noelle Fujii-Oride